As we told you a few weeks ago, in January we said goodbye to “the Rome of Hispania” and crossed the Mediterranean to focus on Rome’s former nemesis, Carthage. Similar to what we did with our first case study, Baelo Claudia, it is time to take stock of our work on the second case study, Emerita Augusta.

The study of the site at the Gulf of Cádiz posed several challenges and, of course, those of Emerita Augusta has been no less challenging. On the one hand, we have come across an enormous amount of data, both epigraphic and archaeological, of which our WebGIS gives an account! On the other hand, Mérida is still a living city, where present-day buildings are superimposed on ancient ones, making it much more difficult to locate archaeological remains through the satellite viewer and we do not always have the coordinates to locate them exactly. Fortunately, the visit we made last September allowed us to familiarise ourselves with its urban planning and to learn first-hand about the latest archaeological interventions in Late Antique Merida.

Along with this, we have also been working closely with our specialist Frédéric Pouget to introduce a new improvement in WebGIS. As we told you in our first post of this blog, to manage the bibliographic references of the project we are using Zotero, a free software program where we have created a shared library with the members of the project. In the past weeks we have been working together with the database specialists from La Rochelle to link our ever increasing Zotero bibliography with the WebGIS. And finally, after much trial and error, we have managed to introduce this new tool that allows us to simply select the bibliographic references from the list that we already have registered in Zotero. In this way, we no longer duplicate the work of bibliographic registration (in Zotero and in WebGIS) and we avoid errors made by manually entering the references in WebGIS. There are still some little things to be solved, but it’s definitely a big step forward!

But let us return to the banks of the Guadiana. Since Emerita is such a massive case study we can’t give an overview of the whole city in this blog. That would most likely become a book. Thus we focus on three different aspects of the city. First we will look at the basilica of Santa Eulalia as this is a place where archaeology (Ada) and epigraphy (Pieter) meet. Then we will look at the territory of Emerita to see what Pieter has been doing with his love for territories. And lastly we turn the houses in the urban and peri-urban areas of Mérida, the work Ada had to collect, analyse and enter all these into the database.

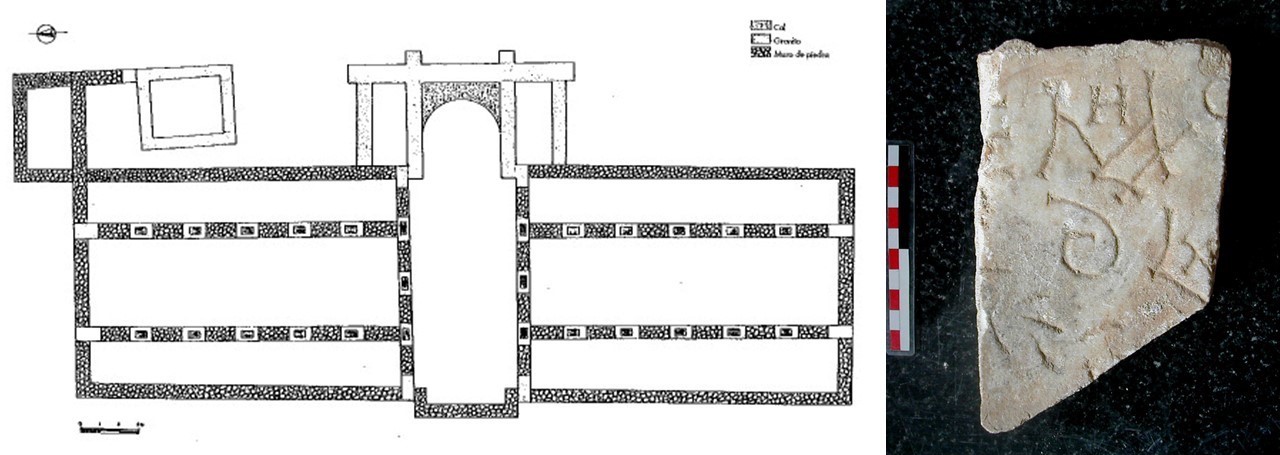

One of the most relevant buildings in Late Antique Mérida is the Basilica of Santa Eulalia constructed in the mid-5th century. It is found to the north of the ancient city wall, just outside in a necropolis initiated in the 4th century. In itself it is not strange to find the early churches in the necropoleis, often they are built close to or on top of the graves of saints. The Santa Eulalia is one of the funerary basilicae, which means that this site began as a Christian cemetery built around the mausoleum that most probably housed the remains of the local martyr, Eulalia.

We can clearly observe this funerary occupation not only through the archaeological remains (the image above speaks for itself), but also through the large number of epitaphs found inside the church. One of these is the threefold inscription mentioned in one of our tweets. The reason for being buried inside, or at least close to, the church is the belief that being in the vicinity of a saint or martyr would help your position as a Christian. At the day of resurrection the connection with the saint would get you into the right ranks.

Near the Santa Eulalia we find another building of interest: the Xenodochium. According to the Vitas sanctorum patrum Emeretensium the bishop Masona had a xenodochium constructed in 580 for the “the pilgrims and the sick poor” (VSPE V. III 4), which has been identified with the building to the east of St Eulalia, archaeologically dated to the second half of the 6th century. Its layout does indeed look quite different from what we know of a church and the location outside the city fits the idea of a place for foreigners (indicated by the xeno- in the name, from Greek ξένος). Could the pilgrims refresh before entering the city and maybe even stay at the xenodochium? When turning to the epigraphy we are a bit confused. Many funerary inscriptions were found in the area around the xenodochium. Now in itself it is not strange to find funerary epigraphy in an extramural area, this is where we expect the necropoleis. And it is also quite common for urban sprawl to be constructed on top of necropoleis. Nonetheless, the funerary epigraphy found near the xenodochium dates to the same period as the construction of the building. This raises questions on the use of this building. If it is a hostel or hospital, why are there graves around it? What is the relation between the building and the graves?

The territory of Emerita Augusta is not an easy subject. The first problem we encounter is establishing the territory of (Late Antique) Emerita. The territory we have currently in our database is derived from the work by Cordero Ruiz (2010). Our data for the territory is partially derived from the PhD thesis by Cordero Ruiz (2013) and from the PhD by Franco Moreno (2008). Both these give us an extensive catalogue of entries with archaeological data and some inscriptions for the territory. As we can observe from our entries, this information is concentrated in the southwest sector, which led us to wonder whether this was a bias created by an unequal study of the territory or whether it responded to a historical reality. The concentrations of epigraphy seem to indicate that we are indeed dealing with a real distribution of the remains. This distribution is not all too surprising, it follows the banks of the Guadiana. The northern parts of the territory are quite rugged as we are in the western part of the Montes de Toledo. It is of interest to note that most churches in the territory are within 20 kilometres, or four hours walking. To the southwest we find two churches quite far away, at roughly 60 kilometres, two days walking from Emerita. Such findings need more attention! Something for the territory group to compare with other case studies with such large territories.

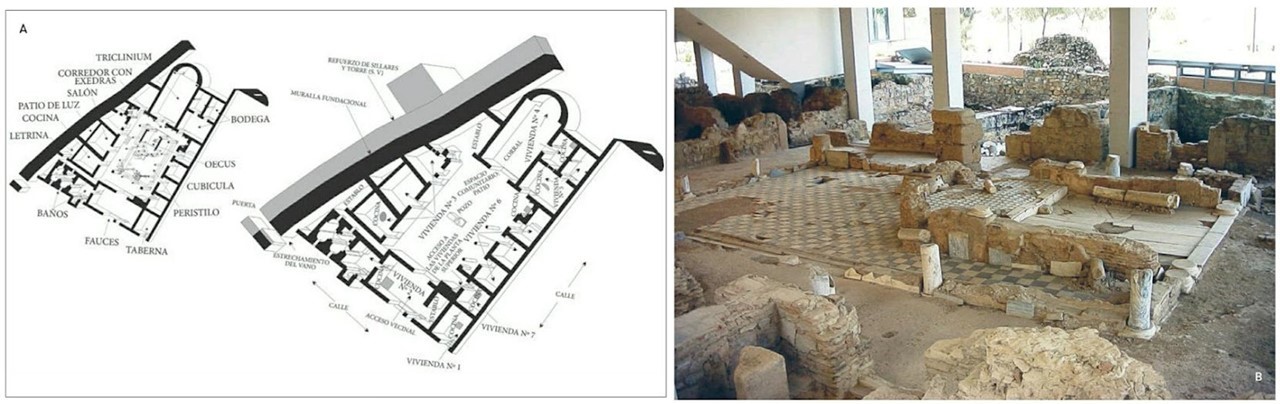

The analysis of the Late Antique houses of Emerita is not an easy task either, especially due to the immense amount of data available. Fortunately, we have recent and exhaustive studies on this subject, especially the doctoral thesis by Corrales Álvarez published in 2016. If we examine the chronology of these houses, we can quickly observe that most of them date from the 3rd-4th centuries and that, from the 5th century onward, the total number of domestic buildings clearly decreases. However, it is equally true that a large number of these domestic buildings from the Late Roman period are only partially known, thanks to the discovery of mosaics or some walls. Even so, we have a fairly large corpus of well-preserved dwellings from the 3rd-4th centuries that allow us to observe socio-economic differences and differences in location within the city. On the one hand, we find domus with rich mosaics and wall decorations that seem to be located mostly within the city walls. On the other hand, more modest domestic buildings have also been found, which also had spaces for productive and agricultural activities, located outside the walls. However, there was a clear change from the 5th century onward. The number of domus, or houses in the Roman tradition, still in use declined and new domestic spaces proliferated inside the walls. These new dwellings often occupied old buildings and show long sequences of use, ranging from the 5th to the 8th century. This is undoubtedly an interesting phenomenon that we must contrast with the dynamics of the other case studies. Is it an exclusively Hispanic phenomenon, or are similar patterns observed in North Africa? Can we identify these patterns in a specific type of city, such as those that had capital status, or is it a generalised phenomenon?

In any case, it is clear that the study of Mérida has allowed us to make great strides in our knowledge of late antique Hispanic cities, while at the same time raising new questions for comparative analysis with the other case studies. So now, with all these concerns in mind, it is a good time to turn to Africa. And what better place to start learning about urban dynamics on the southern shore of the Mediterranean than through one of its largest metropoleis, Carthage.